A recent course assignment dealt with the relationship between characters and readers. The instructor said a character doesn’t have to be the reader’s friend, or even be someone the reader likes. The premise was that women fear writing characters that aren’t nice. I’m sure there are women writers like that; it’s a topic for another post.

The instructor’s opening statement about being friends with the reader, though, led to a good discussion with my friend, author Susan Schreyer.

If I don’t like the protagonist in a book I rarely finish. But what does it mean to ‘like’ the character? Is that character seen as a friend? Or is the character someone you relate to? And how important is that to a story?

In The Heart-Shaped Box by Joe Hill, the protagonist is not someone I liked at all. But I kept reading. Why? Well, because he got a ghost off eBay. Seriously, because the author did an excellent job of slipping in tidbits of character that made me hope the guy would be redeemed. The guy was a ‘real’ character with lots of flaws. Believable in other words.

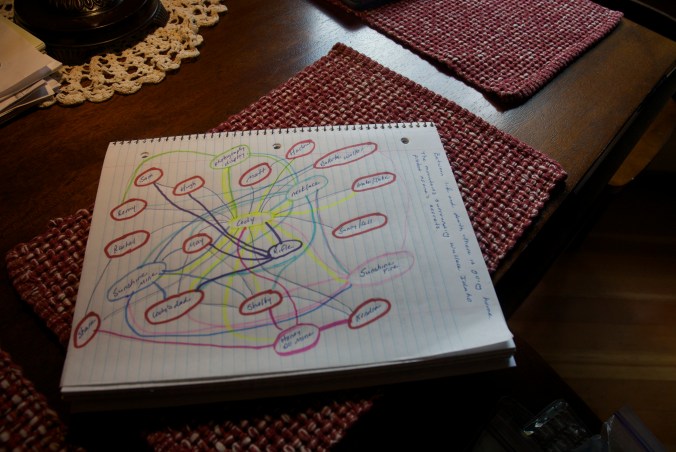

Susan feels there’s a blurring of lines between liking a character and being able to relate to one. She thinks being able to relate is more important, and also easier to achieve in writing. The more traits a character has that are shared with a reader, the more the reader can relate. We also talked about the balance of a character having traits one can relate to with traits one can’t. That balance allows the reader’s opinion to be manipulated.

For example, in Susan’s current work in progress, the next installment in her Thea Campbell series, Thea is being manipulated by one of the characters. If Susan can swing the reader between liking and not liking this character, then the reader will end up feeling just as manipulated by the character as the protagonist is. That draws the reader into the story on a deeper, more emotional level.

Which is exactly why I continued reading The Heart-Shaped Box. I swung between disliking the guy to seeing a glimmer of hope. The author manipulated me, the reader, into sticking with the story by using that mix of likable and non-likeable character traits.

‘Being liked, or being a friend, to the reader feels less important than choosing character traits that propel the character through the story and sets them up with reasons to make the choices they make.’ – Susan

A writer’s responsibility is to create a compelling story. Which, of course, is done through compelling, believable characters. But do you set out to create a character that’s going to be liked? No. If a writer is more concerned about making sure the reader likes a character, then the writer isn’t being true to the story. Or to the character.

Whether a reader sticks with the story, in the end, will be more about how their emotions are manipulated by the story and the characters, than if they feel that character is a friend. And even more so by character traits the reader can relate to, even if there are traits they don’t like.

It all boils down to writing multi-layered, believable characters.